This interview first appeared in Publish News [versión en español], the Spanish-language digital edition of Publishers magazine, in August 2025. [© The Authors]

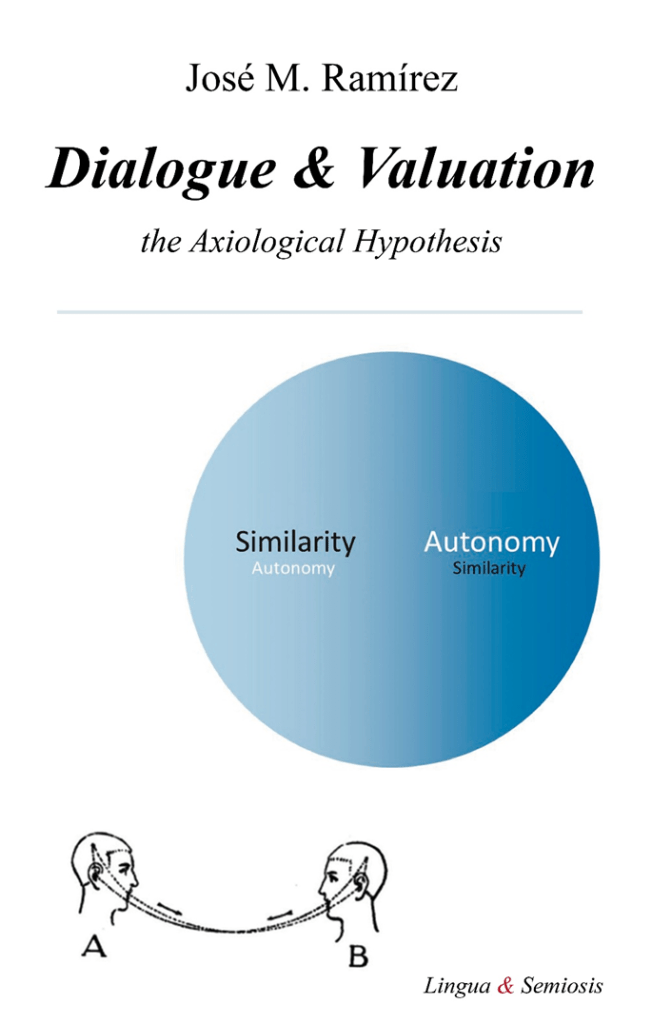

In Dialogue and Valuation: The Axiological Hypothesis (Lingua & Semiosis 2024), José M. Ramírez presents a bold thesis that organically brings together philosophy of language, semiotics, and humanistic pragmatics in a journey toward the valuational foundations of human dialogue. His lucid, elaborate, and highly theoretical essay argues that all linguistic interaction is governed by two essential principles: Similarity and Autonomy. Through an interdisciplinary approach that integrates figures such as Habermas, Halliday, and Van Dijk, and is enriched by an analysis of the work of Ramón y Cajal, Ramírez invites us to rethink the foundations of thought, art, and ideology.

Your work posits that human dialogue is governed by the principles of Similarity and Autonomy. How do these concepts reconfigure our understanding of linguistic interaction?

In non-formal language, the axiological or valuational hypothesis holds that interlocutors are similar and autonomous. We value each other.

Saussure founded contemporary linguistics at the beginning of the 20th century by proposing a modern language, in his case French, as the norm for the broader process of exchanging meanings that we call language. It was a methodological decision, to avoid the dispersion of linguistics into specialties.

However, the meaning we compress into words is just the tip of the iceberg of everything we express and communicate. A single word suggests a thousand images. There is a whole series of elements of context, of reality, both cultural and cognitive, that make it possible to produce and understand a simple statement.

Over the last century, there have been several proposals regarding the pragmatic norms of language, which have been rejected one after another. I argue that Similarity and Autonomy are these norms. These principles of value are abstractions of a whole series of characteristics and features present in our exchanges, which I have observed in numerous texts of all kinds.

In the context of the so-called “humanistic pragmatics,” what place does emotion occupy in rational and scientific dialogue?

This is a difficult question, almost impossible to answer in a few lines. Emotion is usually understood as a brief and intense emotional reaction. I like to use the example of Archimedes of Syracuse’s magnificent “Eureka!” Can there be scientific thought without wonder, without surprise? We know that two plus two equals four, although sometimes circumstances, like Orwell’s character*, force us to shout it out. It is not emotion that is the obstacle to scientific knowledge or truth, but the thousand masks of interests and ideology.

Let us understand emotion, in its etymological sense, as a movement of the spirit. Human beings tend to idealise ourselves, sometimes sensing that our thinking is ethereal, alien to our bodies. In reality, language and thought have a social and cultural basis and a biological, neural basis. Underlying everything is a physical basis, a permanent vibration of things. We are microcosms, intelligent organisms that exchange meanings in a cultural ecosystem. This also applies to scientists. We are humans, not gods! Truth itself is an ideal to which we aspire. There is a movement, an emotion in search of truth, which is always elusive.

Without empathy, there is no full understanding. Placing ourselves in an experience or perspective that is not our own is essential to understanding a new statement, even if we do not agree with it. This cognitive empathy is evident in the analysis of scientific texts. The very act of reading a text is dynamic, requiring a movement of the spirit, an emotional fluctuation. It is true that the formal statements of science tend to neutralise the expression of emotions, but that key and that stimulus are always there.

Do you think that Habermas’ Universal Pragmatics failed precisely because it did not consider the evaluative-emotional dimension that you highlight?

Every true philosopher, like every true scientist, knows that their theories are subject to debate and that, in the best of cases, they will be nuanced and rectified. And Jürgen Habermas is one of the great philosophers in history.

Thinkers such as Philip Kitcher have already pointed out this shortcoming in Habermas’s theory of communicative action, which has been widely questioned in recent decades in the field of philosophy. I have been fortunate enough to come to his thinking with the baggage of very current linguistic theories. Habermas’s theory is already valuational, but linguistic analyses offer evidence that there are more spheres of value than those indicated by him.

The axiological hypothesis is based on an in-depth study of the work of Ramón y Cajal. What do his scientific texts reveal about the links between art, science, and value?

All statements and texts, whether in art or science, are valuational. There can be and there is art in science, as in Cajal’s beautiful drawings of neurons. However, the formality of a scientific text does not reproduce reality itself, but rather measures or evaluates it and makes it understandable to an interlocutor. What differentiates scientific and artistic activities is above all the prevailing purpose, the dominant goal: science seeks the truth about a phenomenon, while art seeks to represent some kind of beauty. Truth and Beauty are principles of value.

Can you explain how visual language, urbanism, or music also respond to the value structures you propose?

At the heart of all language there is an experience and an intention, which is, so to speak, the driving force, the one that pulls the train of language and carries everything else with it: it is a purpose, a desire.

I will try to give just a few examples and suggest some elements for thought.

Just as reading a text is dynamic, a good painting or a beautiful photograph invites us to follow a path. We don’t see, we look, we soak up the image with emotion. The artist often places himself in the viewer’s perspective: he takes that step back, brush and palette in hand, moving away from the canvas to look at it from a distance. In this way, he anticipates our gaze.

Music is the most physical and emotional of languages. Pure emotional vibration, pure feeling. It is often said to be a universal language, although I think this is not entirely true. The classical musical cultures of India and Europe are far apart. To an Indian, accustomed to more nuanced sound values, the piano of Beethoven or Chopin may sound out of tune. Of course, this cultural gap can be bridged. An Indian can surely end up enjoying a good piano concert, just as a European or an American can enjoy a sitar melody.

Urban planning is an activity in which the motivating function of values is fundamental. Lets think of the enormous impact that an urban development project has on dialogue and social interaction. The planning of a square, a park, a road, a bridge connecting the two banks of a river. I am reminded of the excellent novel The Bridge on the Drina by Ivo Andric.

As I attempt to argue in Dialogue and Valuation, democracy is the system that institutionalises humanistic values, that is, dialogue. I believe it is no coincidence that the first known urban planner in history, Hippodamus of Miletus, was responsible for planning the port district of Athens, the first democracy in history.

What are the political implications of a theory of language that places equality and freedom as the foundations of universal dialogue?

The theory of dialogue and valuation completely abandons misunderstood, metaphysical individualism, as well as communitarian interpretations of equality. Neither is freedom characteristic of an isolated self, nor does the mere fact of being members of a community make us equal. On the other hand, it points out that equality and freedom are activated simultaneously in dialogue, in social interaction: they are inseparable. They are not ideological principles, specific to groups, but dialogical, as they emerge in dialogue.

Your essay points to a redefinition of the concept of ideology. How do you distinguish between social valuations and ideological constructions?

The big problem with talking about ideology today is that the term is contaminated by politically unscrupulous uses. I would like to clarify that an ideal is a very abstract, even vague, type of value, not an ideology, and that an ideology cannot be defined as a mere system of ideas or images. A taxonomy of birds is not an ideology. Not every socio-political group is necessarily ideological. A system of social and political ideas can be called a thinking model or idearium (“ideario” in Spanish). Not everything is ideology. My analysis has led me to define ideology as a process of group restriction of dialogue and valuation. I will try to explain myself and will have to elaborate a little.

Categorization is a necessary and powerful tool for identification. Every person is very complex, and we can be categorised in many ways: by our physical characteristics, tastes or preferences, work, income, family origins, nationality or religious affiliation, even by our mood, and so on. In social categorisation, we include the person in a more or less organised human group. We continually evaluate other people and our interlocutors socially, sometimes explicitly, verbally, and other times implicitly, silently. However, in general, our actions are multifactorial, which does not prevent us from being aware of our actions and, therefore, responsible. By attributing an act to a single social category, one can fall into a type of reductionism, a vulgar sociologism. A possible side effect of this tool is that by identifying, for example, the perpetrators of a criminal act by their religious affiliation, nationality, gender, ethnicity, or other social categories, there is a tendency to extend that act to all members of that human group.

It is necessary to point out that individuals do not create ideology. A person may have developed a prejudice against members of a human group because of a previous bad experience. This is an understandable attitude. It is institutions and organised groups that have the capacity to produce and impose ideology. I think a key question that must be answered when categorising is whether there is a cause-and-effect relationship between the social group and the act. Does the social group legitimise such criminal acts, encourage them, cover them up, order them…? If this is not the case and an inappropriate or abusive categorisation is repeated, prejudice tends to spread about all members of that group. Dialogue between members of the two groups begins to break down.

Ideological prejudice undermines the bridge between two social groups and can lead to a serious emotional rift within a community. John Dewey already observed this process on the eve of World War II. Them and us. Them, the ones who steal, who lie, who murder; us, the ones who are robbed, deceived, murdered. Them, the ignorant; us, the knowledgeable. They, the ones who cannot control their emotions; us, the emotionally stable ones. It is not the only ideological resource, but it is a very common one: stereotyping and prejudice.

War is ideological by definition. If a political system of ideas is geared towards the partial or total breakdown of dialogue between different groups, then it could indeed be called ideology. Totalitarian systems are ideological: the state invades privacy to the very core of consciousness, suppressing the autonomy of the individual and preventing them from valuing their own context. Two other extreme historical examples come to mind: the class-based ideology that sustained the old regimes in Europe, and the traditional Hindu caste ideology. And Plato. The model of the state he describes in his later works is a society of isolated corps that do not communicate with each other, a type of technocratic corporatism. It was his response to the humanism that inspired Athenian democracy.

In short, I believe that every organised social group is exposed to a dual tendency: a humanist tendency, open to dialogue and valuation, and an ideological tendency, which restricts them. Even democracies, which protect pluralism, are exposed to this tension.

You state that “we interlocutors are similar and autonomous.” What challenges does this statement pose in an era of polarisation and communicative tribalism?

We are living in a time of a very evident crisis in the liberal democratic model. I somewhat agree with Churchill when he said, in other words, that democracy is the least bad of all possible systems. I would add that it is a dynamic system, which we can either improve or worsen. In political terms, we are moving from the category of adversary, with whom we debate, to the category of enemy. Some irresponsible intellectuals whitewash authoritarian systems and theocratic or integralist regimes. I believe that the great political question of our time is why democracies have lost their appeal and why old authoritarianism is advancing once again. The theory of dialogue and valuation can help to highlight the ideological processes of action-reaction in all social spheres and, above all, to seek creative solutions to the thousand problems and shortcomings of our societies.

Your approach dialogues with the functionalist and contextual currents of Halliday and Van Dijk. How do you articulate this theoretical dialogue with your axiological proposal?

Systemic and functional linguistics provide the best description of language grammars, the resources of attitudinal valuation, and linguistic and semiotic processes. Without Van Dijk’s contextual model, which integrates the social and the cognitive, I would not have been able to develop the axiological hypothesis. I am eternally indebted to these two theories, which were my starting point and are unavoidable in analysis. The evaluative proposal is eclectic: it also incorporates elements of phenomenology, cognitive linguistics, relevance theory, Voloshinov’s dialogism, and Saussure’s notion of linguistic value. I hope that in the future other linguists and semiologists from other fields will make their contributions.

What, in your opinion, is the greatest contemporary misunderstanding surrounding the concept of “value,” and how do you hope your essay will help to clarify it?

From Platonian metaphysics, ther is a tendency to identify valuation with the subjective. This is not the case. In philosophy and science, too, some prejudices are difficult to abandon. I believe that 2,500 years of obstinacy is enough. Valuation and value are interactional.

To value, in the simplest and most general way, is the act of measuring reality. A value is an image of the world; the model or mental scheme with which we value an aspect of things.

A serious misunderstanding of these concepts indeed persists. At this moment, I am applying the theory of dialogue and valuation, or humanistic pragmatics, to the analysis of texts on astronomy and physics. Physical magnitudes such as length or mass are evaluative. In the model of humanistic pragmatics that I am developing, these magnitudes constitute a sphere of value. If I say that something is very big, I am making an attitudinal evaluation that expresses my own perspective or position; if I say that it measures 30 meters, I am making an ideational evaluation, using the conventional unit of measurement that we call a meter.

Saussure’s notion of linguistic value is fundamental. A category, for example the word “house,” is a linguistic value. If I say “there is a house in the clearing in the forest,” the house I evoke or remember and the one my interlocutor conceptualises are different. What I have done is simply to mentally include that thing that was in the middle of the forest in the group or category “house.” I have classified it. Perhaps I was wrong in my valuation, because it is not a dwelling, but a small building for storing farm tools. These categorisation errors reveal the valuation. The value “house” is a stabilised and agreed-upon category in a linguistic community. Syntactic positions are also evaluative, the result of a measurement of reality. Other values are very complex and abstract, such as the principles of Truth, Beauty, Similarity, and Autonomy, or even composite values, such as a model letter or article. Or a model interview.

* Winston, main character in George Orwell’s novel 1984, is tortured into saying, and even thinking, that there are five fingers where only four are shown.

+ Information on the Spanish Course on Humanistic Pragmatics

Factoría de la Lengua

Un comentario